The Loaded Weapon Doctrine: A Reporter Remembers

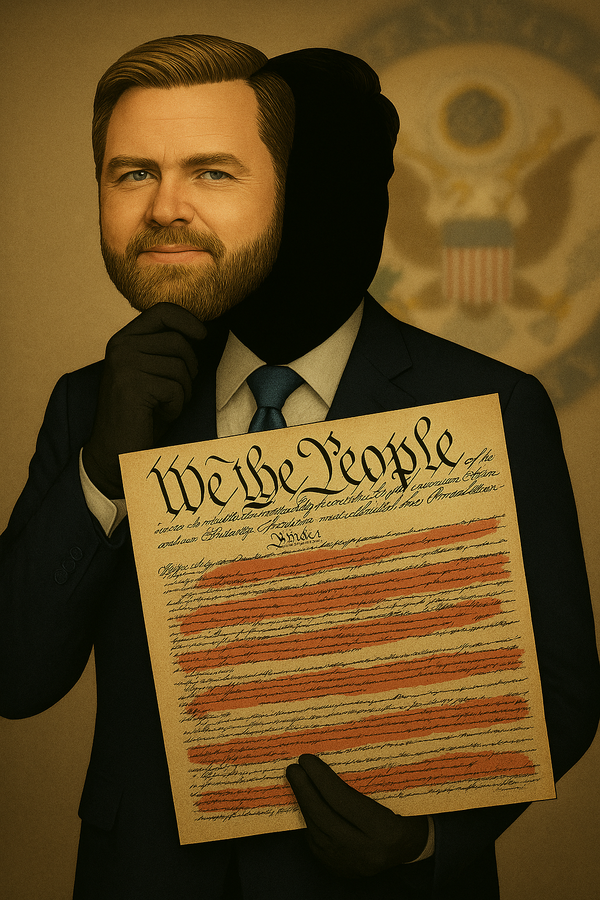

A president shrugs at due process. Migrants vanish without hearings. A reporter remembers when this happened before—and what it cost the country.

Good evening.

There is a moment when a president is asked a question so fundamental to our system of government that the asking should seem unnecessary, and yet the answer reveals everything.

“Do you, as president, have a duty to uphold the Constitution?”

The fact that such a question must be asked in 2025 is itself a measure of how far we have traveled from certain shared understandings about American democracy.

"I don't know," came the response. "I'm not a lawyer."

I am reminded of another moment in our history when constitutional principles yielded to fear and expedience. In February 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the removal of more than 120,000 Japanese Americans from their homes to internment camps.

No trials were held. No evidence of individual wrongdoing was required. Their crime was simply their ancestry.

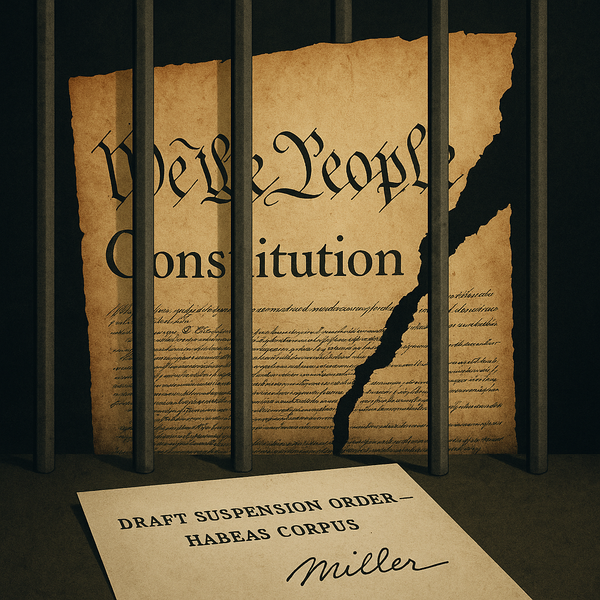

Today, we witness legal residents of the United States—some who have lived here for decades, raised families, and contributed to their communities—being deported to foreign prisons under a law drafted in 1798. The Alien Enemies Act was conceived for use during declared wars against foreign nations. Now it is being deployed against individuals labeled as “gang members,” often without evidence, without hearings, without the opportunity to contest these designations.

Consider Kilmar Abrego Garcia, a Maryland resident with legal protection from deportation, who was seized without warrant and delivered to El Salvador’s Terrorism Confinement Center. The Department of Justice later admitted this was an “administrative error,” yet fought court orders to return him. Or the hundreds of Venezuelans detained at the Bluebonnet Detention Center, handed documents in a language many cannot read, given mere hours to prepare, then shipped to foreign prisons.

"The principle of racial discrimination lies about like a loaded weapon, ready for the hand of any authority that can bring forward a plausible claim of an urgent need."

— Justice Robert Jackson, dissenting in Korematsu v. United States (1944)

The same might be said of the principle that due process can be abandoned in the name of security.

I recall reporting on the aftermath of the internment, speaking with Americans who lost everything—their homes, businesses, savings, and dignity—because wartime fears overwhelmed constitutional protections.

The Supreme Court’s decision in Korematsu stands as one of its most widely condemned rulings.

In the cold light of history, what seemed necessary in a moment of fear was revealed as a grave injustice based on prejudice rather than evidence.

Yet here we are again. The Justice Department claims individuals do not deserve hearings because they belong to gangs—a claim many only learn of after deportation. When courts examine these cases, they frequently find no evidence supporting these designations. One judge called the government’s deportation scheme a process that "denies even a gossamer of due process."

The Supreme Court has consistently held that the Fifth Amendment’s protection applies to all "persons" within U.S. jurisdiction, not merely citizens.

Even Justice Antonin Scalia, no liberal idealist, wrote in 1993 that it was “well established that the Fifth Amendment entitles aliens to due process of law in deportation proceedings.”

But when reminded of this legal reality, the President responds that it would require “a million or 2 million or 3 million trials”—as though the scale of the task justifies abandoning the principle.

The architects of Japanese internment similarly argued that individual hearings would be impractical given the number of people involved and the urgency of the perceived threat.

History has not looked kindly on that reasoning.

We know now that when Japanese Americans finally received an opportunity to challenge their detention, virtually none were found to pose any threat to national security.

Today, when migrants deported under the Alien Enemies Act obtain legal representation and hearings, many are discovered to have no gang affiliations at all.

What connects these historical threads is a willingness to sacrifice individual rights for what appears, in the moment, to be collective security.

What is sacrificed is not merely the liberty of those directly affected, but something fundamental to our constitutional system: the principle that government power must operate within legal constraints, that assertions require evidence, and that everyone deserves a fair chance to contest accusations before their freedom is taken.

"I have since deeply regretted the removal order and my own testimony advocating it, because it was not in keeping with our American concept of freedom and the rights of citizens."

— Earl Warren, former California Attorney General and later Chief Justice of the United States

How many of today’s actions will become tomorrow’s regrets?

How many lives will be irreparably damaged before we remember, once again, the lessons we once thought permanently learned?

Good night, and good luck.

Channeling Murrow’s voice for today’s America — not his words, but his principles.